The aim of this page is to provide potential PhD students in my group with an informal overview of what doing a PhD is like. This page isn’t so much about the PhD application process or the research areas my group works in (for that please check out this information page), but more broadly about what a PhD is about. This overview is tailored towards a PhD in robotics, in my group – it will be similar to many other areas of computer science, but less similar to PhDs in other areas like the humanities, social and biological science areas. At the end of this page is a growing set of answers to frequently asked questions.

There is also a video version of this information page:

Introduction to the PhD

A typical PhD is a 3 year (they sometimes go longer than 3 years but 3 years is the aim), full time research project where you get to dive deeply into a fairly specific research topic. There may be other professional activities during your PhD like tutoring, internships at companies and so on, but your primary activity will be conducting research.

An Opportunity to Dive Deeply into a Problem

A PhD is an opportunity to deeply investigate an interesting, not yet fully solved problem or topic area. You’ll start as a relative novice, but by the end of the PhD the idea is that you are the world’s foremost expert in that focused topic area. In my group that could be any topic from advancing bio-inspired neural networks for robotic perception and navigation to camera-based positioning technologies for autonomous vehicles. By its conclusion, you’ll be ideally equipped to then make further advances in that area post PhD, whether that be through a university role, a role in industry, government, or as founder of a start-up.

But a PhD is not just about advancing knowledge and capabilities in that narrow area of expertise, but also about the range of skillsets you’ll pick up along the way: working independently and as part of a team, reviewing existing research, formulating hypotheses, problem-solving, creating new algorithms, techniques or robotic systems, learning to bridge disciplinary boundaries, communicating at a professional level across multiple mediums: verbal, written, formal and informal, and many other skills. Members from our group regularly give presentations to international and national audiences, including competing in presentation competitions like the 3 Minute Thesis Competition – Stephen was a QUT finalist in 2020, and Somayeh is a Faculty of Engineering winner in 2021.

You’ll also develop the critical ability to handle and manage uncertainty and the ups and down of conducting new research, which never proceeds smoothly the entire time. PhDs in robotics and related fields also typically involve a significant element of creativity, in order to create new approaches and concepts.

All these skills and experiences will serve you well regardless of your career path beyond your PhD – it’s worth noting that the majority of PhD graduates in robotics and related areas do not end up as academic professors at universities, instead going to leading tech companies and startups.

A Big But Not Too Big Undertaking

For many people, a PhD will be the most intense and focused project they will have done up to that point in their lives. But it’s also important not to become intimidated by the magnitude of it – a PhD is just one, admittedly significant step, on a journey that will continue well beyond your PhD, whether you stay in academia, found a startup, or go into industry or government.

A Fantastic, Sociable Learning Environment

A PhD takes place in a fantastic learning environment, and many students report that the learning curve is steeper but more exciting and fulfilling than their undergraduate degree.

Firstly, you’re paired with several supervisors who are often world class experts in the field you’re researching in. But it’s not just research that they’ll help you develop, but also all the other aspects of being a researcher – teamwork, communications, project management, planning, risk mitigation, and dozens of other vital skills.

Secondly, you will learn just as much if not more from your peers and colleagues. A large robotics group is filled with other academics, postdocs, PhD and Masters students and undergraduates – and on a day-to-day basis they’ll be the ones you’ll chat to the most, who’ll share tips, code, even food. They’ll share your elation at making a major research breakthrough and empathise when your research (temporarily) hits a dead end. There’s also a significant social element here as well – chatting, games nights, sport and so on – and it’s entirely up to you how much you want to engage.

Endless Opportunities Within and Beyond Your PhD

It’s quite common for PhD students to spend time at other labs, either within the country or even overseas. Likewise, PhD students will often pause their PhD to take advantage of internships at companies, which can often become full-time careers later on.

For just a few examples:

- Jake did an internship at leading AI research centre Google Deepmind in London during his PhD, then returned to work there full time as a Research Scientist upon submitting his PhD

- Stephanie flew across the world to take up a postdoctoral research role at Orebro University in Sweden working in applied robotics

- Will interned at Oxford University, return there as a postdoc and then went on to lead the mapping and localization team at major self-driving-vehicle startup Nuro.AI in California.

- Zetao joined ETH Zurich in Switzerland and then Facebook.

- Dana followed her PhD with postdoctoral roles and then became an academic lecturer at Swinburne University.

- You can stay close to home too – for example, Adam joined Fortune 100 company Caterpillar as an automation engineer in Brisbane after working on a joint project with them following his PhD.

Key Stages and Milestones

The key milestones for a PhD vary from university to university and over time, but here’s a typical outline for an Australian university like mine:

Application process: You submit your CV, other credentials including any existing research experience and publications and a research plan developed in association with a nominal supervisor. The primary aims here are a) to get accepted into the PhD program and b) to win scholarship funding (and potentially fee waivers) to enable you to perform the PhD full time. You can also bring your own funding in terms of a scholarship or sponsorship from your current employee.

Initial Report (3 months in): Known as a Stage 2 report at my university, 3 months into your PhD you write a short report outlining what you’ve found after conducting a comprehensive literature review of the topic area, along with a proposal of what you’ll do for the rest of the PhD.

Confirmation (12 months): at this point you’ll write a detailed report with a very comprehensive review of past research, a detailed proposal for what specific research questions you’ll be addressing and a detailed plan for how you’ll achieve this. You’ll also include an update on your initial research performed during the first year. You give a 45 minute formal confirmation seminar to a panel who will provide feedback on how you’re going.

Main PhD Component (0 – 36 months): There’s no such thing as a “typical” PhD but you could say that a “typical” PhD might have three major and distinct research contributions, that are performed in order, and which build to some extent on the previous one. Each of these outcomes would be associated with a publication outcome, which brings us to…

Publications (6 – 36 months): the tangible outputs of your PhD are research publications. In robotics, a typical aim would be to have two lead-author international conference papers in venues like the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation or the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, and one lead author journal paper (often submitted near the end of your PhD) in a top tier journal like International Journal of Robotics Research, IEEE Transactions on Robotics or IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters.

Getting top tier publications accepted is not trivial, with many of these venues having acceptance rates below 30% or 40% – when (not if) you do have papers rejected, you can use the feedback from the reviewers to improve the work and resubmit it to another venue in an improved form. Generally speaking, this process of feedback and improvement works well, even if it can seem frustrating or disappointing at the time of a rejection.

Here’s an example of a “typical” robotics publication:

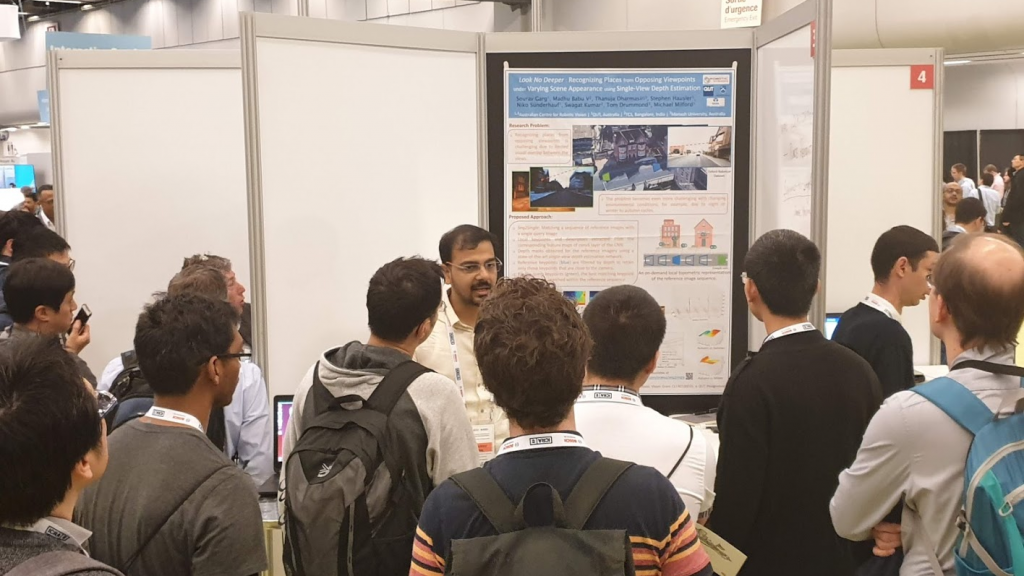

Conference Trips: as a first author on an accepted international conference paper, you will most likely get at least one opportunity to attend the conference overseas and present your paper during an oral or poster presentation. These trips are fantastic experiences where you get to mingle with the leading researchers in the world, learn about all the state of the art research being carried out and network and develop connections for future collaborations. You’ll also get to meet all the leading companies and start-ups in this technology spaces and conference conversations often lead to internships, jobs or even investment funding. There are also potential opportunities for local conference attendance as well

Thesis Manuscript: The final outcome of your PhD is a thesis document, typically a 100 – 300 page research report. It comprises an Introduction, Background section and then several chapters, one per major research contribution. It ends with Discussion and Future Work.

There are two primary types of thesis: “by monograph”, and “by publication”. By monograph means you write the entire document from scratch, whilst from publication means you insert your research papers as the middle chapters, along with some extra introductory material at the beginning of the chapter. Which format you choose depends on your preference and also on whether you’ve met the required number of published or submitted papers to do it “by publication”.

Here’s a recent example of a PhD by publication from Sourav.

Final Seminar: Shortly before you submit your thesis, you’ll do a final formal seminar where you present your thesis in a 45 minute talk to a formal panel. Whilst a formal affair, it’s not as serious an event as a thesis defence (USA-style) – the panel is there to give feedback on your progress, your thesis document and what needs to be changed before final submission.

Submission and Revisions: once your thesis is submitted, the examiners (chosen by your supervisor) will typically take about 2 months to review the thesis. The outcome of this are examination reports – basically a heap of feedback. More formally, you’ll typically either have your thesis accepted “as is”, with “minor revisions” (takes a couple of weeks to address) or “major revisions” – bigger changes required and may go back to the examiners.

During this time, there’s a range of options. Students often continue their research as a research assistant, pseudo-postdoc, but can also take some time off to do something different after concentrating so hard on the PhD for the previous few years.

Funding During Your PhD: A typical PhD student will have a scholarship of some form, either awarded during the initial application process or associated with a specific research or industry project. Sometimes students can get more than one type of scholarship (a second one is sometimes referred to as a “top-up”). Scholarships are typically quite competitive, and rely on factors like your GPA (and which university it came from), any relevant publications and prior research experience in the area.

Income can also be supplemented with part-time tutoring or research assistant roles, although there are limits to how much work you can do whilst also receiving a scholarship. Much or all of the funding is often tax free, which means that your effective remuneration, while not as high as a typical high end graduate job, is more than enough to live in a share house, run a car or pay for transport, socialise with friends and go on the occasional holiday.

Work Life Balance: This varies from PhD to PhD, but many students end up working on average as hard as an entry level engineering job, albeit with a different type of work. The work is somewhat unevenly distributed – towards PhD and publication deadlines the work will often be more intense, with less intense periods afterwards. Many of these deadlines (especially publications) are shared across a group so everyone often bonds over the mutual experience of pushing towards a research and publication deadline. At the beginning of the PhD regular contact and office hours is usually important to get off on the right start, but as you become experienced and more productive some flexibility is possible, as long as you are making good progress and are happy with how you’re progressing.

Awards and Accolades: PhD students have the opportunity to win best paper awards and other prizes. For example Stephanie won the Siganto Medal, Sourav won both a Dean’s Commendation for Outstanding Thesis and a SAGE publication award for their PhD research, and Ed won a Dean’s Commendation for Outstanding Thesis.

A Brief Word of Caution

A few words on what a PhD is not: A PhD is not a 3 year period of completely unfettered, free-roaming research. The program of research has to be somewhat structured (even if it changes later based on progress and set backs) and it must produce multiple peer-reviewed research publications.

Although most PhD students will be diving deeper into a topic than they’ve ever before in their lives, you will sometimes still need to stop investigations before reaching a fully satisfactory conclusion, and you will need to prioritize and triage which of a number of interesting research directions to pursue – you can’t do them all within an entire career, let alone within the confines of a PhD.

For perfectionists, the process of publishing your research can also sometimes feel somewhat unsatisfying, in that they have raised more questions or ideas for future investigation than they have answered, and you can’t possibly investigate them all before submitting the paper. Finally, sometimes you may feel like some of the things you need to do to get published – for example rigorous benchmarking against existing techniques – are distractions from conducting open-ended and free-ranging investigations.

This is all fine and indeed the nature of conducting good, evidence-based research – there’s always fascinating ideas to explore and never enough time. As long as you are aware of this reality and can manage it, you can prosper in and enjoy a PhD.

What Next?

After finishing a PhD, people go on to a wide variety of roles, ranging from academia, industry, startups or government, with some examples given in the above section. Many end up in roles that are technically different to their PhD topic, but which benefit from the general skills and experience developed during the PhD. One of my past students Edward even went on to commence a career in medicine.

Recap

A PhD is typically a wonderfully fulfilling and occasionally frustrating journey. Most but not all people end up completing their PhD, with people who do leave early doing so for a huge range of reasons ranging from a PhD not being a good fit for them, to the many opportunities in industry and startups available today.

It’s important to talk to a range of people who’ve engaged in the PhD process to get a diverse and balanced view of what it’s like, and hopefully the information on this page has also provided some perspective. For me personally, a PhD was one of the most enjoyable, exciting and fulfilling times in my professional career and I will always hold many fond memories of what was a pivotal period in my life.

Frequently Asked Questions

How will a PhD change my job prospects?

The answer to this changes from year to year but the general rule of thumb is that a PhD will open up new opportunities simply not accessible without one. Some people think that PhDs remove job opportunities – this is generally not true if managed correctly. For example, if you finish your PhD and decide to go into an industry role not requiring the PhD, you’ll probably need to have some coherent and convincing answers as to why you’re taking that path – interview panels will often bring it up.

There is also the ongoing debate over qualifications versus capability. Some organisations are relaxing their criteria at the graduate intake level – not necessarily requiring a degree if relevant aptitude can be demonstrated. However this approach is still currently in the minority – qualifications still count for a lot in most cases. A PhD qualification is often the minimum entry requirement for many high tech R&D jobs.

Can you get these roles without a PhD? Yes, of course – we are just talking generalities here.

Can I do my PhD part-time?

Yes you can but there are some caveats. Part-time status will reduce your access to some opportunities like scholarships, and can also influence things like whether you get a student discount card for public transport. The answer to this question also depends on what you’ll be doing with the rest of your time. For example, some people do PhDs part-time while working full time. This is extremely challenging – not impossible – but should not be attempted lightly. Doing a PhD part-time in conjunction with part-time or casual work is more feasible but still difficult.

Can I financially give up my full-time job to do my PhD?

I can’t give financial advice here but the answer to this will generally depend on your specific financial circumstances. Successfully taking on a PhD requires minimal distractions from the rest of your life – if you are constantly living pay check to pay check and stressed about rent and bills, it’s not a good environment in which to take on the challenging nature of a PhD.

Should I choose a junior or senior supervisor?

The general rule of thumb here is this: capable junior researchers will have more time to dedicate to your supervision, will learn quickly on the job, but will lack some of the experience a senior supervisor has. Senior researchers will (generally) have less time, but will have far more experience and wisdom to share with you. Importantly, they’re also more likely to have a large team of postdocs and other PhD students who will be your academic support family for the duration of your PhD – something a junior academic may not always have. Often the best combination is a senior and junior academic supervisory team – where often the senior academic will start as principal supervisor but will nurture the junior academic into a principal supervisor role. That’s how I, and many others, got their start in supervision.

All bets are off of course if it’s a bad supervisor – and, just like any profession, there are always bad examples. You can mitigate this risk by talking to the supervisor first.